Music: "Halos" by Lars Leonhard, courtesy of the artist and Ultimae Records.

Lars Leonhard:

Ultimae Records:

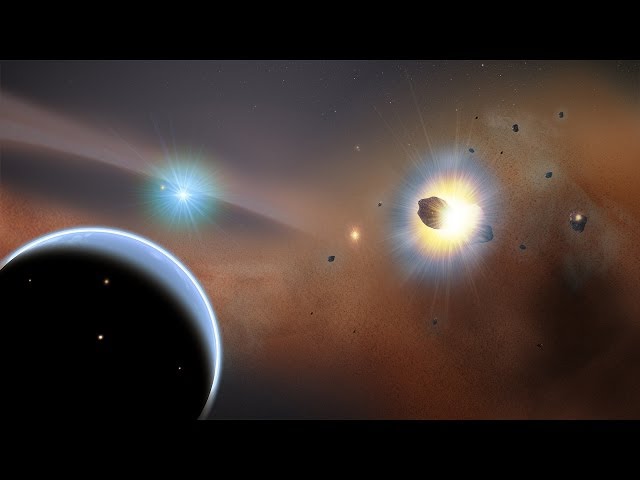

An international team of astronomers exploring the disk of gas and dust the bright star Beta Pictoris have uncovered a compact cloud of poisonous gas formed by ongoing rapid-fire collisions among a swarm of icy, comet-like bodies. The researchers suggest the comet swarm may be frozen debris trapped and concentrated by the gravity of an as-yet-unseen planet.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers mapped millimeter-wavelength light from dust and carbon monoxide (CO) molecules in a disk surrounding the star. Located about 63 light-years away and only 20 million years old, Beta Pictoris hosts one of the closest, brightest and youngest debris disks known, making it an ideal laboratory for studying the early development of planetary systems.

The ALMA images reveal a vast belt of carbon monoxide located at the fringes of the system. Much of the gas is concentrated in a single clump located about 8 billion miles (13 billion kilometers) from the star, or nearly three times the distance between the planet Neptune and the sun. The total amount of CO observed, the scientists say, exceeds 200 million billion tons, equivalent to about one-sixth the mass of Earth's oceans.

The presence of all this gas is a clue that something interesting is going on because ultraviolet starlight breaks up CO molecules in about 100 years, much faster than the main cloud can complete a single orbit around the star. Scientists calculate that a large comet must be completely destroyed every five minutes to offset the destruction of CO molecules. Only an unusually massive and compact swarm of comets could support such an astonishingly high collision rate.

The researchers think these comet swarms formed when a as-yet-undetected planet migrated outward, sweeping icy bodies into resonant orbits. When the orbital periods of the comets matched the planet's in some simple ratio -- say, two orbits for every three of the planet -- the comets received a nudge from the planet at the same location each orbit. Like the regular push of a child's swing, these accelerations amplify over time and work to confine the comets in a small region.

This video is public domain and can be downloaded at:

Like our videos? Subscribe to NASA's Goddard Shorts HD podcast:

Or find NASA Goddard Space Flight Center on Facebook:

Or find us on Twitter:

Lars Leonhard:

Ultimae Records:

An international team of astronomers exploring the disk of gas and dust the bright star Beta Pictoris have uncovered a compact cloud of poisonous gas formed by ongoing rapid-fire collisions among a swarm of icy, comet-like bodies. The researchers suggest the comet swarm may be frozen debris trapped and concentrated by the gravity of an as-yet-unseen planet.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers mapped millimeter-wavelength light from dust and carbon monoxide (CO) molecules in a disk surrounding the star. Located about 63 light-years away and only 20 million years old, Beta Pictoris hosts one of the closest, brightest and youngest debris disks known, making it an ideal laboratory for studying the early development of planetary systems.

The ALMA images reveal a vast belt of carbon monoxide located at the fringes of the system. Much of the gas is concentrated in a single clump located about 8 billion miles (13 billion kilometers) from the star, or nearly three times the distance between the planet Neptune and the sun. The total amount of CO observed, the scientists say, exceeds 200 million billion tons, equivalent to about one-sixth the mass of Earth's oceans.

The presence of all this gas is a clue that something interesting is going on because ultraviolet starlight breaks up CO molecules in about 100 years, much faster than the main cloud can complete a single orbit around the star. Scientists calculate that a large comet must be completely destroyed every five minutes to offset the destruction of CO molecules. Only an unusually massive and compact swarm of comets could support such an astonishingly high collision rate.

The researchers think these comet swarms formed when a as-yet-undetected planet migrated outward, sweeping icy bodies into resonant orbits. When the orbital periods of the comets matched the planet's in some simple ratio -- say, two orbits for every three of the planet -- the comets received a nudge from the planet at the same location each orbit. Like the regular push of a child's swing, these accelerations amplify over time and work to confine the comets in a small region.

This video is public domain and can be downloaded at:

Like our videos? Subscribe to NASA's Goddard Shorts HD podcast:

Or find NASA Goddard Space Flight Center on Facebook:

Or find us on Twitter:

Be the first to comment